Verena Loewensberg

Verena Loewensberg (born 1912 in Zurich, Switzerland, where she died in 1986) grew up in Sissach, after her family moved there in 1918. She studied weaving, embroidery, design, and color theory at the Gewerbeschule in Basel from 1927 to 1929. After this, she continued her training with the weaver Martha Guggenbühl in Speicher, before studying modern dance at Trudi Schoop’s school in Zurich. She also took classes at the Académie Moderne in Paris in 1935. In 1932, she married the graphic designer Hans Coray and began working mainly in advertising art and fabric design. This work allowed her to earn a living for herself and her two children after her divorce in 1949. Loewensberg, who was passionate about music (especially Jazz), opened a record store called City Discount in 1964, which she ran until 1970 and became famous all over Switzerland. Music, modern dance, and her many journeys abroad all had a long-lasting impact on her oeuvre, which consists of roughly 500 oil on canvas paintings, 60 prints, several watercolors and drawings, and two sculptures.

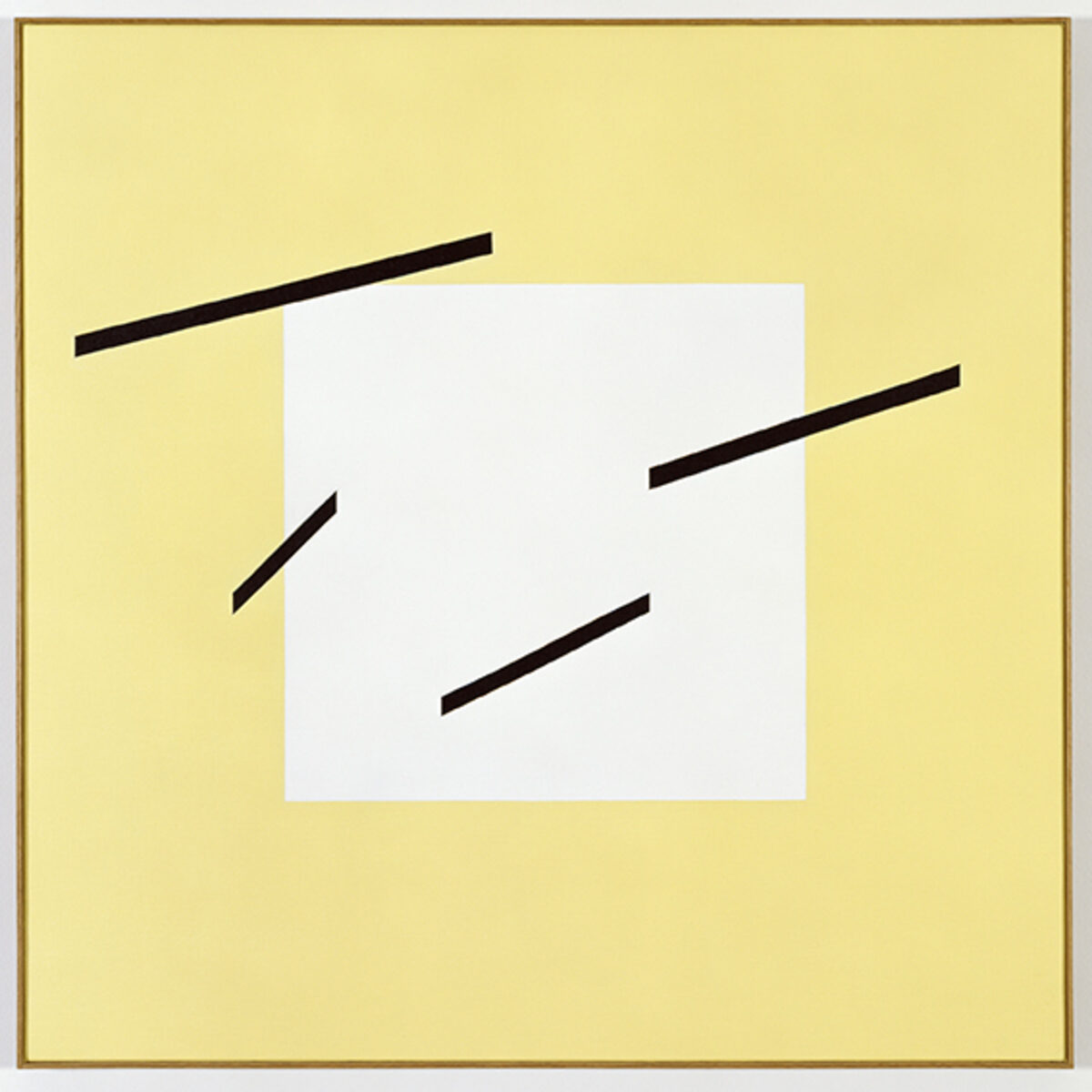

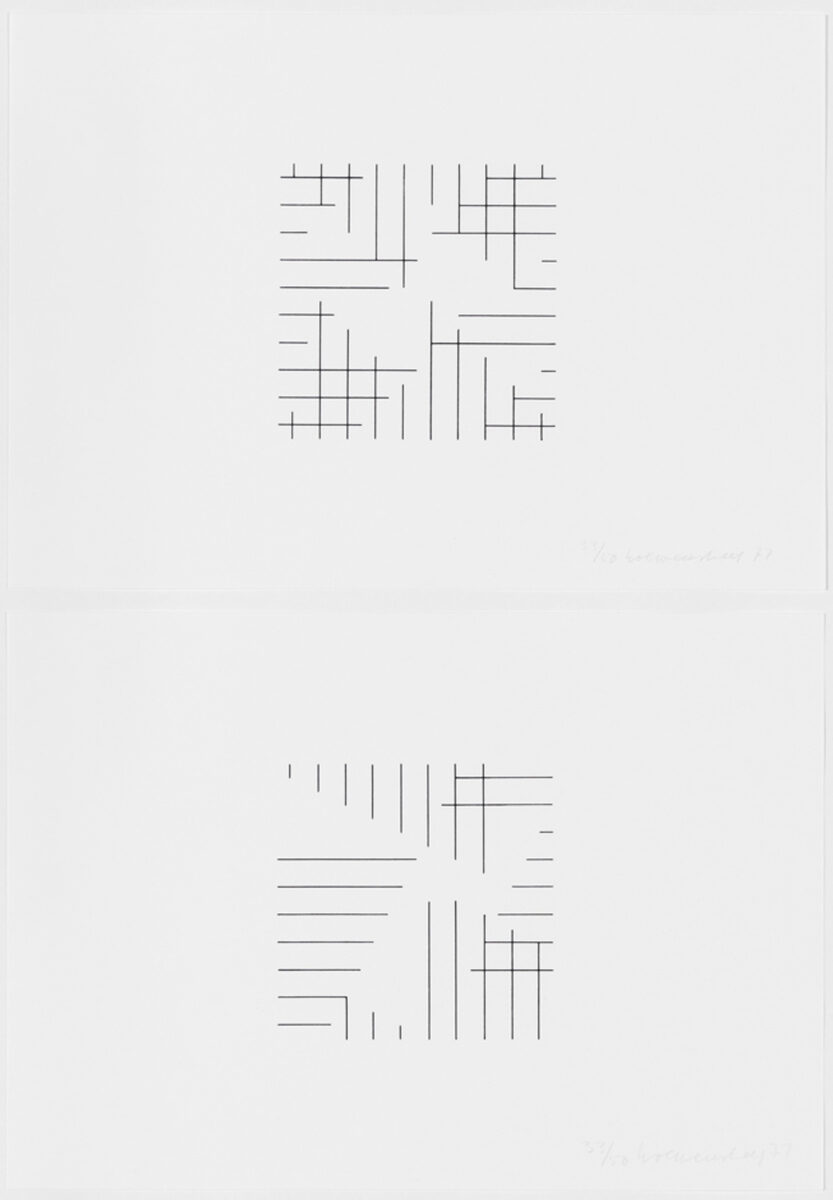

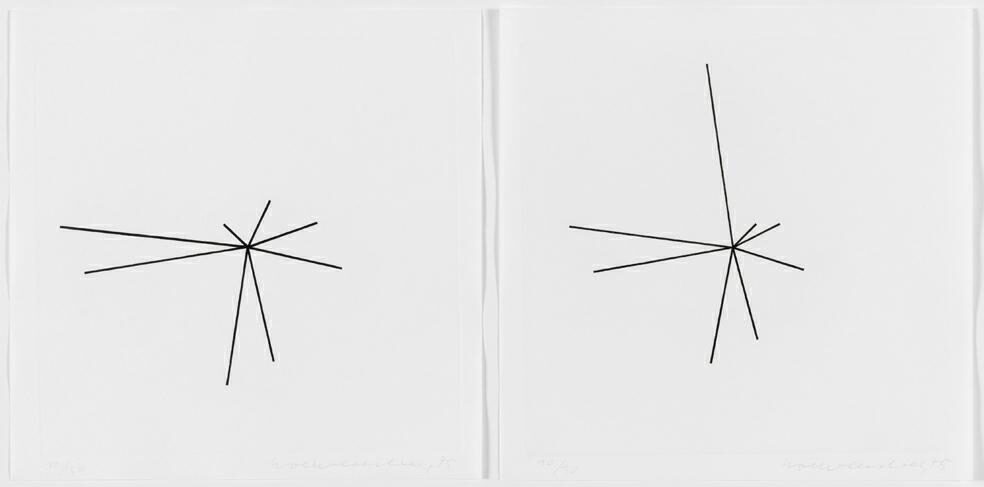

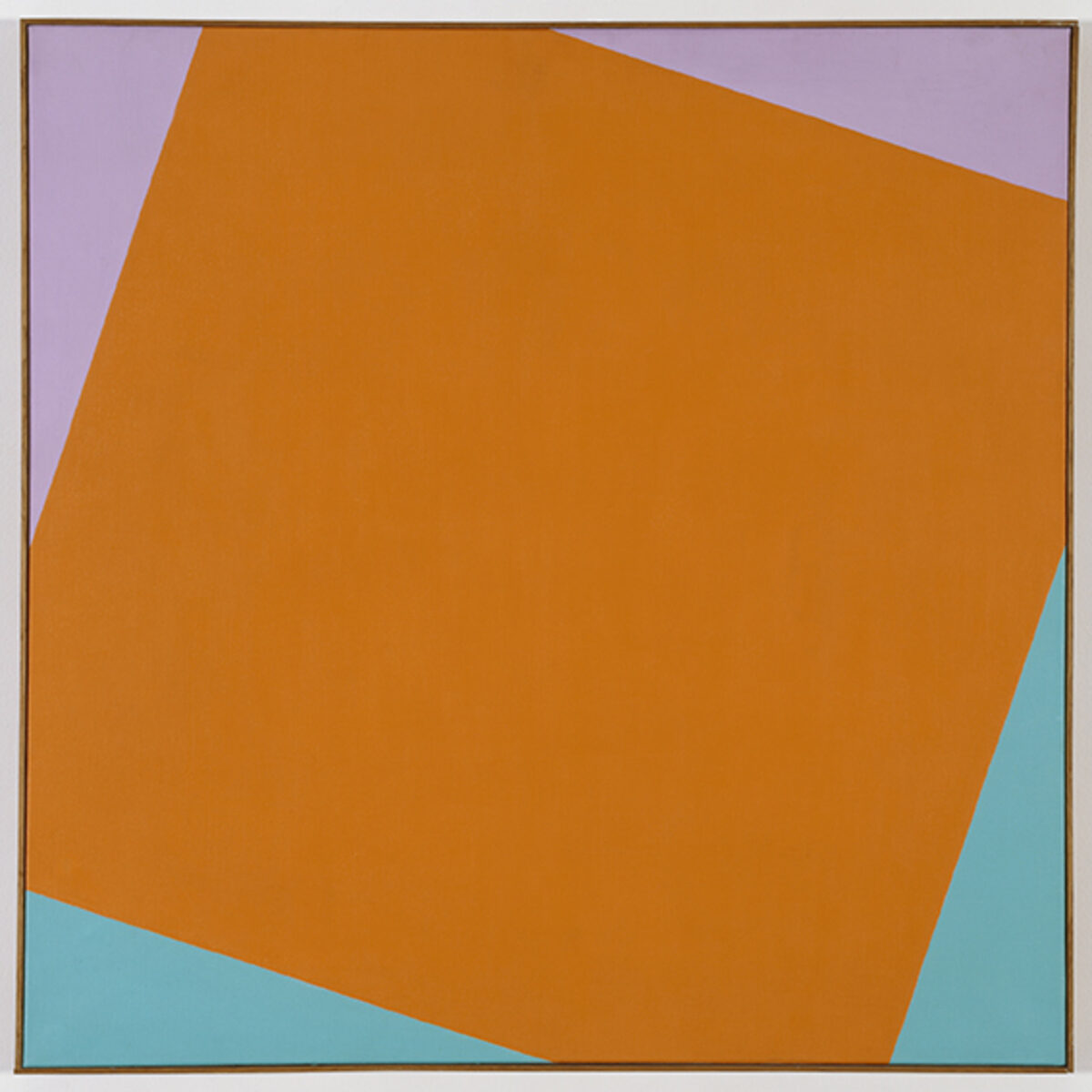

After a few early experiments with representational and abstract art, in 1936 Verena Loewensberg began to work with the pictorial language of geometry, testing it in her graphic works at first. Then, in 1944, she focused solely on painting, which she had learned on her own. In the first decade of her artistic career, she relied on the Abstraction-Création movement as a model, but she soon began to develop her own independent and multifaceted style. This was always characterized by Loewensberg’s search for a pictorial connection between rationality and feeling, and systematics and inventiveness. Relying on simple, basic forms (polygons, rectangles, triangles, and circles) and the simultaneous integration of a broad range of themes (line to plane, figure and ground, symmetry and asymmetry, center and margin, progression and rotation), her work developed in stages alternating between playful formations (“Untitled,” 1978), minimalistic reduction (“16 gravures,” 1975), hierarchical austerity, meditative introspection, and powerful expansion (“Untitled,” 1963). The color in her compositions played an essential role as a psychological and energetic component. In addition to black and white and primary colors, Loewensberg also worked with a rich palette of carefully modulated shades. This masterful control of color went hand in hand with a painting style she had perfected that made the essential meaning of the cohesion between color and form clear. This is especially the case in her final, mature works with bi-colored polygonal formations.

Verena Loewensberg was the sole woman in the inner circle of the so-called Zurich Concretists (together with Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Richard Paul Lohse). Although she participated in many exhibitions, she had a different status in the male-dominated scene of the Concretists, also due to her disposition and her particular understanding of art. She did not gain broader recognition until the 1970s, when her work began to be admired for its diversity. In 1981, she became the first woman to have a solo exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich. Her work is now represented in many well-known museum and private collections. The Verena Loewensberg Foundation, which manages her estate, was established in Zurich in 2014.

Elisabeth Grossmann

After a few early experiments with representational and abstract art, in 1936 Verena Loewensberg began to work with the pictorial language of geometry, testing it in her graphic works at first. Then, in 1944, she focused solely on painting, which she had learned on her own. In the first decade of her artistic career, she relied on the Abstraction-Création movement as a model, but she soon began to develop her own independent and multifaceted style. This was always characterized by Loewensberg’s search for a pictorial connection between rationality and feeling, and systematics and inventiveness. Relying on simple, basic forms (polygons, rectangles, triangles, and circles) and the simultaneous integration of a broad range of themes (line to plane, figure and ground, symmetry and asymmetry, center and margin, progression and rotation), her work developed in stages alternating between playful formations (“Untitled,” 1978), minimalistic reduction (“16 gravures,” 1975), hierarchical austerity, meditative introspection, and powerful expansion (“Untitled,” 1963). The color in her compositions played an essential role as a psychological and energetic component. In addition to black and white and primary colors, Loewensberg also worked with a rich palette of carefully modulated shades. This masterful control of color went hand in hand with a painting style she had perfected that made the essential meaning of the cohesion between color and form clear. This is especially the case in her final, mature works with bi-colored polygonal formations.

Verena Loewensberg was the sole woman in the inner circle of the so-called Zurich Concretists (together with Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Richard Paul Lohse). Although she participated in many exhibitions, she had a different status in the male-dominated scene of the Concretists, also due to her disposition and her particular understanding of art. She did not gain broader recognition until the 1970s, when her work began to be admired for its diversity. In 1981, she became the first woman to have a solo exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich. Her work is now represented in many well-known museum and private collections. The Verena Loewensberg Foundation, which manages her estate, was established in Zurich in 2014.

Elisabeth Grossmann

Works by Verena Loewensberg